According to the ISO standard, gears can be made in one of twelve accuracy classes. The application is the starting point of the class that the gear should represent, and this is when it will fulfill its application function.

Starting with the simplest dependencies, such as speed, safety standards or noise level, which affects the quality of work. Therefore, the gear must be made the most precisely when

-

it has higher peripheral speed during the operation,

-

the transmission plays a more responsible role (e.g., aircraft transmissions are made, due to strict safety standards, much more precisely than agricultural ones),

-

the noise level must be lower, e.g., due to the well-being of a person working in close proximity to the gearbox.

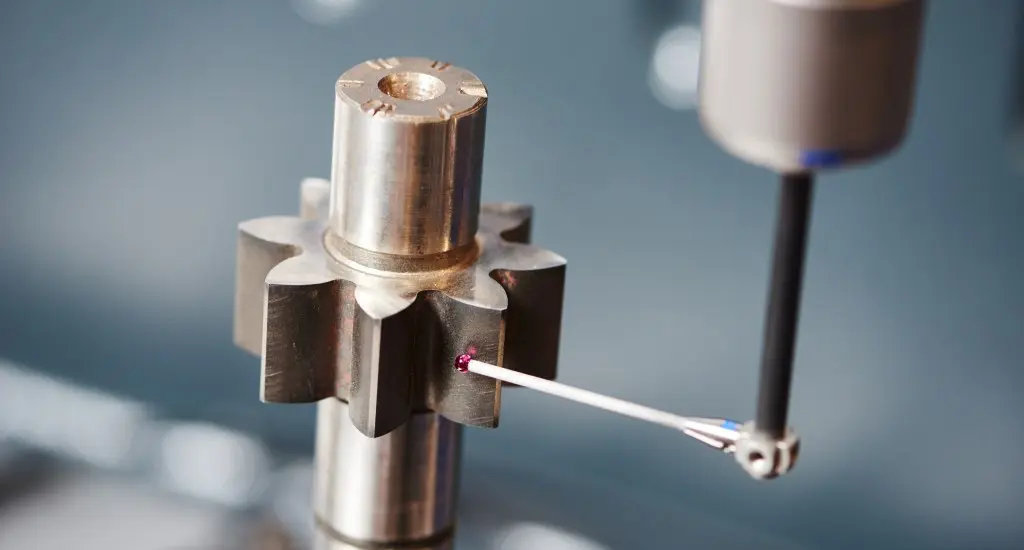

Accuracy classes of gears as a function of peripheral speed

The choice of the accuracy class depends on the peripheral speed of the gear, the higher the peripheral speed, the more precisely the gear should be made. However, it does not consider turbine gears with very high accuracy, gears to measuring instruments, which, despite the lack of high rotational speed, must be very carefully and precisely made, as well as gears with high low-noise operation.

Proper selection of the accuracy of the gear is very important due to the non-linearly growing cost of production along with the class increase. As a standard, it is assumed that with typical gear generating machining (hobbing with a hob cutter and shaping with a Fellows shaper cutter) even the 6th class of accuracy can be achieved. Theoretically, it is possible, but it often requires very precise and expensive tools, rigid and modern CNC machines and ideal working conditions. From a practical point of view, often despite meeting all the conditions, machining with the tool in the highest possible class of accuracy (in the case of hobs AAA class) and having a modern machine, it turns out to be a problem to achieve even the 7th class of accuracy.

Gear transmission accuracy class (pol. “Klasy dokładności”) depends on the application

Influence of the gear accuracy class in relation to the grinding time

The economic analysis shows that the highest possible accuracy class should be achieved direct after machining, e.g. hobbing (if grinding can be avoided, it should be eliminated), on the other hand, if grinding (usually hardened wheels) is still required, then it should be achieved in a class as close as possible to that required for further cost reduction.

Grinding the teeth is still the most popular method of finishing gears, but apart from it, there are also other methods:

-

burnishing (gears in a soft condition) - the hard wheel burns the tooth surface, eliminating some of the more superficial scratches, but the downside is having a separate burnishing tool for each type of machines part (gear), which generates large costs of purchasing tools for various types of production. This method is practically not used anymore,,

-

shaving (soft wheels) - the tool (shaving cutter with grooves cut along the teeth) improves the waviness of the tooth sides and the smoothness of the surface in relation to hobbing or shaping. In addition, it eliminates the error of the profile, and the error of the scale is also reduced. This method is used nowadays very rare, also due to grinding,

-

skiving with a carbide hob cutter - a tool with a negative rake angle, milling (hobbing) with high cutting speeds, finishing the side flanks of the teeth. The standard allowance is 0.15-0.3 mm / flank, the toothing before skiving should be roughly machined to the full depth. A new tool is needed for each new part; hence this method is mainly used in mass production,

-

tooth honing - a tool made of a material similar or adjacent to the material of the grinding wheels, usually used after grinding. Its purpose is to remove scratches that cause micro-vibrations,

-

Power-Skiving - machining with a special tool structurally resembling a shaper cutter, either in one step, with a monolithic carbide tool or in two steps, first with a tool with carbide inserts and then with a finishing tool made of powder steel.

The least accurate methods of gear manufacturing are forming methods, milling with a gear milling cutter or end mill.

Sources:

[1] - Ochęduszko K., Koła zębate, tom 2 wykonanie i montaż, Wyd. VI (reprint), 3 dodruk, WNT, Warszawa, 2015, ISBN 978-83063623-05-0